Ming tells about his encounter with Wensum Lodge during his schoolboy days attending the Chinese school set up by the Chinese Association of Norwich in the late 1980s, and his language learning at the time.

The Chinese School in Norwich

My parents come from the New Territories in Hong Kong, which borders China. At home they spoke a Chinese language called Hakka, although Cantonese would be the main language in Hong Kong along with English. They came over to Britain during the 1970s, and moved down to Norwich when I was very young. Most of the Chinese in Norwich at the time would’ve come from Hong Kong and spoke Cantonese and possibly Hakka. Dad’s boss, Mr. Tang, was one who spoke Hakka.

As such, Hakka would be my first spoken language; linguistically you pick the language of your home environment. English would come with school, but Cantonese was a bit more interesting and perhaps unconventional. In the 1980s, the Chinese community had access to programmes of Hong Kong’s main commercial broadcaster, TVB, on video tape. They had an office in London which video tapes could be rented. The workers would club together and rent the tapes which circulated amongst their families; the dads would work in the restaurants or takeaways and the mums and children would be at home. The programmes were in Cantonese, so as an inquisitive child I wouldn’t know what was being said but I would try to mimic the sounds. I even managed to learn a song which I have vague memories of. I would ask mum ‘what does that mean?’ repeatedly because I didn’t understand Cantonese, which probably got very annoying. But to truly acquire a language you need feedback. So my parents would typically speak Cantonese outside in the community, and Hakka at home. Think of it like how Spanish is widely spoken in the USA amongst the Hispanic population, and they would likely speak English in the workplace. Hakka and Cantonese has a similar relationship.

In all likelihood I didn’t have much or any English when entering playschool; I knew Hakka and some Cantonese. I remember I would have been a child with special educational needs due to my lack of English in Avenue First School. I think I was one of two children who had a teacher take us specifically for English, while the other children had English, I assume. I can’t remember much of what we were taught, but I do remember puzzles being a part of it. I’m unsure how long I attended these lessons, but I’m sure I didn’t have them in Avenue Middle School. Oddly, my English was perhaps the best amongst the boys in the class in third year.

My first experience of French would’ve been third year in Avenue Middle School. I do remember we had one French lesson and that was it for the entire year! So there was minimal French at the time. But at CNS or Eaton, City of Norwich School as it was awkwardly called at the time, French was part of the curriculum. We only got German as an option at GCSE only if we proved ourselves competent enough in French, if memory serves. I didn’t hesitate and switched to German because I found French difficult, and I dislike our French teacher’s method of teaching. She kept referring to things she taught her class last year, and I wasn’t in her class at the time.

The Chinese school at Wensum Lodge

My acquisition of Cantonese was a little less conventional. The video tapes would have aided in it, but formal learning only really began when the Chinese Association in Norwich established a Chinese school or class in Wensum Lodge. It would be taught in Cantonese with traditional script for writing. I think the Chinese Association wanted to bring the community together. Not all the families would’ve met, and while we all spoke Cantonese most of the children probably didn’t know how to read or write. I believe this would have been the main weakness for the children in Norfolk at the time. The Chinese school would have children from around Norfolk attending it on Sunday. It fostered a stronger sense of community and enabled contact between different families. More so for the mothers, I believe the dads would’ve probably met in the casino at Great Yarmouth at the time.

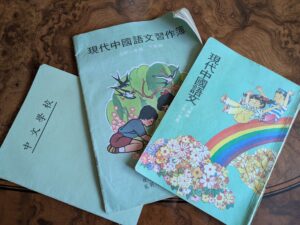

While we learnt Chinese at Wensum Lodge, my memories of those days are hazy at best. Most of my memories of the school itself are mainly of a few teachers and some of the things we did. We had these handwriting books which had square grids to help guide our strokes for the Chinese characters. In Chinese script, the brushstroke order is important. Typically it’s from top to bottom, from left to right. I’d imagine a character can be wrongly written if a stroke is out of order, but how you tell from the written page is another matter. It’s like teaching handwriting to children in reception, Year One and Year Two: there’s a certain set of etiquette to correctly write a letter and join letters; only Chinese is perhaps more pedantic. As part of the culture, one of our teachers also introduced us to using the traditional brush with inkstones and bars. We would have to add a bit of water to the stone and then grind the bar to produce the ink before we could write. We would dip the brush into the ink before putting it to paper. But we had to hold our hand off the page in midair, which was really tricky. Imagine writing with a biro but your hand isn’t touching the writing surface. There are masters of Chinese calligraphy who would write perhaps a single character for Chinese New Year as a salutary goodwill message which are absolutely exquisite. But as children, we were just fumbling around and playing as it were. It was unlikely something we would have got to learn at home. And I’m sure it gave some of the Chinese businesses more business at the time too, as we had to buy the brush, inkstone and bar and paper.

I always managed to do well at school when it came down to it at the Chinese learning side of things. My parents were happy with my progress; they’d say the way I write certain characters was very beautiful. Although how much of that was encouragement is another matter. I would say it was relatively neat and conventional. There was homework set which were a few questions after the set text in the book. The question section would have been trickier because there would be characters we weren’t taught. So one trick would be to translate the question into English, or to try and give some meaning to the characters you don’t know. I tried to add words to remind me of the sound of the character. I remember there were two characters which meant to host, and I used the words banana and bag to remind myself of how the Cantonese sounded. If I was really stuck I could always ask mum, but for the most part I would work alone. I might still have the books somewhere in the shed…

With Chinese being a tonal language it makes the tongue more receptive to different sounds and shifts in tone. Chinese dialects, or languages as I prefer, are very distinct to one another. If a pure Mandarin speaker-listener with no experience of Cantonese were to try and communicate with a pure Cantonese speaker-listener with no experience of Mandarin; they wouldn’t understand each other because there’s no common ground except for the writing. The tones and inflections are different. Certain terms and phrases don’t make sense from one to another, even if you use the same words. We only have to look at the phonetic alphabet of different languages to see Cantonese and Japanese have more sounds than English.

Code switching

What’s more interesting is the code switching we do on the fly. Back when the Chinese school was at Wensum Lodge we would ride with another family; they owned a fish and chip shop off Unthank Road at the time. The two brothers attended the school, though I can’t remember if we were in the same class. On the way home, one of them said I’m hungry. Except he was switching between Hakka and Cantonese and the sounds were completely confused and messed up. It was neither one language nor the other. There are points when you switch from one code to another which makes sense. So for lemon tea, we could say lemon in Cantonese and tea in English, but lemon in Cantonese and tea in Cantonese sounds awkward. So for him at the time it all got smooshed up trying to say I’m hungry. Something similar happened at UEA in Japanese with a different student but that’s a different story.

I don’t remember too much about the Wensum Lodge days because it was before I was ten years old. I was probably in Avenue Middle when I started going. I think we had to join someone else to get there, because it wouldn’t have been dad who took us. I think we had to be taken in to where we had to go at Wensum Lodge, as children we could barely find our own way anywhere I’d imagine. I do remember the desks were set up in rows and things like that. Look East came in when it first opened and we had to be on our best behaviour because we might be on camera. If they have an archive and it’s still there, I could probably be seen sitting in the background as the main child was being interviewed. I believe there’s a newspaper clipping which has our headteacher in the article, who happened to be dad’s boss at the time. We lived in the workers’ residence at the time, so family upbringing was a little bit different from the standard at the time.

I remember my first teacher there. She actually owned Jumbo Restaurant, which was at the top of St. Stephens at the car park there. It’s since been sold and did other things. She has passed away since but I’ll always remember her because she was my first experience of formal learning of Chinese. We’d have other teachers since, but Wensum Lodge was the launching pad for us. We moved to Bowthorpe High School which I consider it to be part of its golden age. Then we’d move to Earlham High School, which is now City Academy. Both were closer to home for us, and I think dad started to take us there. There would be a tuck shop at lunch break which the mums ran, and I remember mum doing the tuck shop thing as well. I think the Chinese Association started to tap other people with the teaching.

Chinese students learning teaching at UEA

From what I remember a lot of students from Hong Kong came to study the PGCE, Post Graduate Certificate of Education, at UEA—UEA being a well-known teaching centre—and then return to Hong Kong to teach. We knew many of these students at the time, and I think I was nine when we moved into our first council house where mum would host them on various occasions. Many of them had taken up teaching duties at the Chinese school as well, so it meant more regular usage of Cantonese for me. Mum would have started to go out to work, so would have one of them babysit me during those years. I’d continue to watch video tapes in Cantonese as well. At some point of language acquisition it becomes more about learning new words after gaining fluency. I would still code switch for certain concepts: some things I can say in Hakka, but not in Cantonese; some in Cantonese but not Hakka. In English we don’t have a word for the German concept of schadenfreude, so it’s like that. It’s quite interesting being able to switch between all three though there are only a few people I can do that with, which is a bit unfortunate but life goes on.

Moving to Earlham

I can’t remember when I first started at the Chinese school in Wensum Lodge but I do remember leaving around the age of 14 before GCSEs, which puts us in 1991. The Chinese school had moved to Earlham High School at the time, and the curriculum was the issue. I think because it was a fairly informal venture, there was no strict progression or continuity. With the PGCE students from Hong Kong, it meant the next year you have a different teacher. We would repeat the same exercises, same part of the book again and again when we should be continuing from where we left off. There wasn’t enough continuity there. And by the time of Earlham High School, there were only two of us in my class. In tests, it didn’t matter if I 100%ed it, it didn’t mean anything if there’s only two of you, even if the other scores 99%. It’s not as impressive as being top of a class of 30. In our case, one was top of the class and the other bottom no matter how we scored. It was a bit of a bust. But the lack of continuity and progression led to frustration on our part. I already knew the characters for person, mouth, hand, and moon. Yet term after term it we would repeat person, mouth, person has mouth; hand, person has hand; moon. How about getting to the end of the book? But we didn’t get there; we never did complete the book. So to this day, in the informal formal curriculum we had my written Chinese is still at kindergarten level. Ironically I would learn more Chinese characters via learning Japanese than through Chinese, but that’s a different story.

Thinking back, I spent many years with the Chinese school even though I can’t remember when I started. I get the feeling it was a short while after 1984 or 1986. The Chinese Association held a Christmas party for the school at the Norwich Sports Village, and our teacher at the time had the class learn a particular Hong Kong pop song, or Cantopop song, for our performance. And the song was released about that time. So it was some time after the song’s release.

Back at Wensum Lodge, we did have one of the adults join us who was coincidentally one of mum’s friends. We always joke that she was my classmate despite our difference in age. It’s a nice little joke to share. So while most of the learners were children, it catered for everyone and wasn’t discriminatory about age or anything.

Interestingly enough, I believe this occurred after we left Wensum Lodge, so either at Bowthorpe or Earlham; but there was a woman who helped the adults with their English. Basically she held English lessons while the children were learning Chinese. Mum was one of those who would take up those classes at the time. So it was certainly a very community focussed, because it would help the community with their everyday lives and for the children to understand their roots.

The early years are what I consider its golden age, as the community feel and camaraderie was strong. At break times the children could mingle and go down to the tuck shop. Back then, Channel 4 had these film seasons. One year they were showing Hong Kong films on Saturday at midnight. I remember this because one of the films was A Chinese Ghost Story, and a lot of us had watched it the night before, so it was the talk at break time. There was a scene which involved a lot of slime and woe betide any of us who were having a snack at the time. You weren’t hungry after that scene!

Ming Cheung talking to WISEArchive on 12 March 2025 in Norwich. © 2025 WISEArchive. All Rights Reserved.